Goodbyes Have Haunted Me

Weeping over my tiny kitty when I know her death is imminent reminds me that mine is, too.

I know 63 isn’t exactly near decrepitude, but consider: I was diagnosed at 28 with the disease that killed my mother, her mother, and her sisters. I’ve lived 13 years longer than my mom and one year longer than my dad. So staring into the kaleidoscopic shards of my own mortality has been going on for a long, long time.

Besides that I was orphaned at 27, another thing you should know about me is that I had a cemetery on the east side of our garage, facing the neighbors, not my mother, for errant animals. Family pets, of course, but also field mice, fallen robins, and even the occasional heroic cricket. I’ve always raged against the dying of the light, even the light of an arthropod.

Goodbyes have haunted me. My sister died when I was thirteen. Stoic through the visitation, I shrieked at the graveside as the dirt thumped onto her. I nearly fell on her grave, unable to process this finality. The dirt is always the worst part. My mother grabbed my arm and pulled me away toward the car. My behavior embarrassed her. I wonder, if she’d known her turn to lie in a casket was barely four years away, she’d have felt differently.

Before they wheeled her into the OR, my mom looked at me—me, her 17-year-old daughter, not her 26-year-old son or her husband—and said, “I’m tired. Tell them to lay me out in my pink dress and scarf.” I shook my head like I could fling that thought into a black hole. “No, that is not happening, because you’re coming out of this, and it will all be fine, and we’ll all be happy again! No!” I ignored her wish to stop fighting death, not to mention the reality that we’d never been happy, so being happy again was a contradiction.

By the time we lost Dad ten years later, my family had become an efficient machine at grief. Before I could even make the seven-hour drive from Minneapolis, they’d divided up his belongings and matter-of-factly told me what would belong to me. They’d learned Elsa’s frigid lessons of don’t feel, conceal extremely well.

The summer after our freshman year of college, my best friend and I were in a car accident. An older woman in one of the other cars died. Knowing she was at fault, my friend reeled at the news, unable to cope with the guilt and pain. I bent my own stitched-up face over my friend’s wheelchair in the ER and said, “God must have had a reason for it to happen.” She glared at me and replied, “I don’t want to know that God.”

It was an incredibly stupid thing to say. I was nineteen and new to the idea of believing in God at all, let alone having a handle on theology and counseling skills.

In the intervening years, I realized I don’t want to know that God, either.

The notion of God as a divine chess master, moving pieces at will and discarding them when they no longer serve a purpose, owes more to our own need for certainty than to the Bible. Because we want there to be a reason for death, we breezily create a God who plans for and executes it. It comforts us little to think this way, and it opens a whole host of questions we’re not prepared to face. Yet the human quest for answers in the face of pain insists we find them, and the quickest, most unassailable answer is, “God willed it.”

In that verse made famous because of its brevity, we know that Jesus wept. Specifically, he wept at his friend Lazarus’ tomb. Lazarus had been dead four days, and his sisters, also Jesus’ friends and disciples, grieved the loss of a dear brother and a provider in an unstable world. We understand why they wept. We know why they raged at dying light. But why did Jesus?

Of course he felt sadness at the grief of his friends, but he also knew that their sadness was about to end. So more must be in play. Jesus wept tears of sorrow, groans of anger, over the world he had breathed into existence. In that world, death wielded, and still wields, fear and anguish with a power he never wanted it to have.

Jesus worked against death daily. He went around raising widow’s sons from the dead. He healed with abandon people whom death would otherwise find too soon. He demanded justice for women who might have been killed at the whim of a crowd.

In a final act of rebellion against death, Jesus refused to be held by its snares, spinning past the rising sun a 3000-pound stone meant to guard his tomb and ensure his acquiescence to death.

The only death Jesus ever acquiesced to was his own, and that not for long.

I’ve failed to acquiesce, and I’ve failed to say goodbye well on more than those early occasions. Really, how does one know how to do what we were not created to do? How do we hold the tension between raging against death and seeing people fully enough to let them go?

When our last pair of cats, Merry and Pippin, died, it was within less than two weeks of one another. Appropriate, I suppose, considering their names. They entered our household thirteen years previously as a duo and left it as one. We didn’t even know Pippin had cancer until a trip to the vet because he seemed “off” led to a revelation of pancreatic cancer and an obvious need to let him go right there, without warning or preamble. I sobbed into his fur, then wailed as I felt him stiffen in his last moment. I knew the blessing of holding him through his transition. I felt the desolation of knowing an unexpectedly empty cat carrier on the way home.

Yet worse was Merry a week later, when I was four hours away wedding dress shopping with my youngest daughter. She exited the dressing room expecting glowing reviews, and I turned a tortured face to her, my ear to my phone, hearing that my friend had taken him to the vet when she found him unable to move or care for himself. Joy and grief together in such a small space.

I knew I should have let him go. We knew of his cancer. But Merry was my cat. Pippin was the family’s—Merry was mine from the moment I walked into the humane society room and he came to the front of his cage, cocked his striped head, and pushed it onto the bars for our first head butt. I was devastated that he suffered and devastated that I was’t the one to was with him at the end. That goodbye had been all wrong.

In the beginning, God planted a tree. He also planted humans next to it. Eternal life was intentionally available to them, by nature or nurture irrelevant so long as they could reach out and eat the fruit of it. Post-resurrection, we again have that edenic promise in our grasp. The One “who has destroyed death and has brought life and immortality to light through the gospel” (2 Timothy 1:10, NIV) knows first-hand what it is to die and to live, after all.

That God did not intend our tears is a comfort to me in grief. It’s a balm to know death is a terrible but common side effect of living in a troubled world—not a grand orchestration by a Conductor who wants us all to learn a cosmic lesson in it. He doesn’t like it any better than we do—and that captivates me again with a Creator who created only good and who records my sorrow and gathers my tears (Psalm 56.8).

A couple months after Merry, a larger goodbye rocked us. My mother-in-law had chosen hospice rather than further chemo, and we knew it was time to call the family in to say goodbye. Our last night with her, we sat around the living room of their assisted living apartment, singing her favorite hymns and remembering funny family stories. I watched my daughters comb her hair and give her a last mani-pedi, as gentle as fairy fingers with the grandma they cherished. Dad stood behind her, a hand on her shoulder, tears streaming as we sang, “though sorrows like sea billows roll . . . it is well with my soul.” When we put her to bed, she pulled me close and whispered, “you’re my daughter too. Don’t forget that.” I struggle with goodbyes, but this was the best one I’ve ever witnessed or lived.

Three years later, coming home from a conference, I stopped to see my father-in-law. I nearly heeded his self-effacing admonishment that I not bother to stop so that I could get home before it was too late, a six-hour drive ahead of me in November early darkness. I didn’t heed it. We chatted in that same living room for an hour or less, a tiny blip in the timeline of my days. It was the last time I ever saw him. I’d begun to learn that moments don’t always offer themselves up more than once, and my life motto of “will I regret it if I don’t do this” applied to people as well as experiences.

The Arbinger Institute, in their bestseller Leadership and Self-Deception, talks about being “in and out of the box.” Being in the box means that we see others through the lens of our own experiences and our own hurt. We interact with them based on the muscle memory of our family of origin, for better or for worse. The stress from another area of our life enters the relationship and alters it, despite the other person’s lack of relation to that stressor. When we leave the box, we’re choosing to see the other person as fully human, with all our fears, joys, weaknesses, and strengths. We choose to interact based on our shared humanity rather than our own fears.

Or, if not shared humanity, at least, shared animal life form.

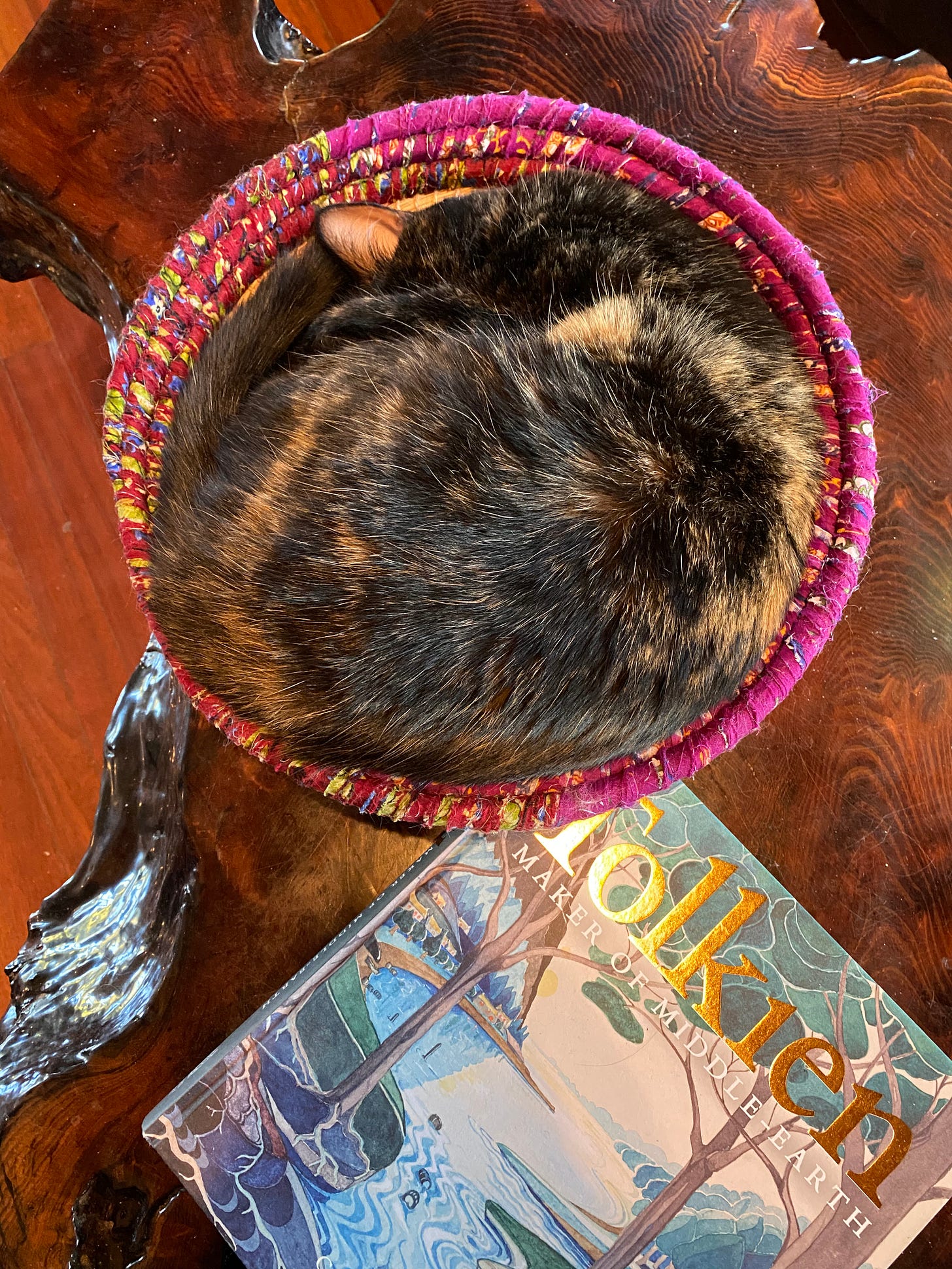

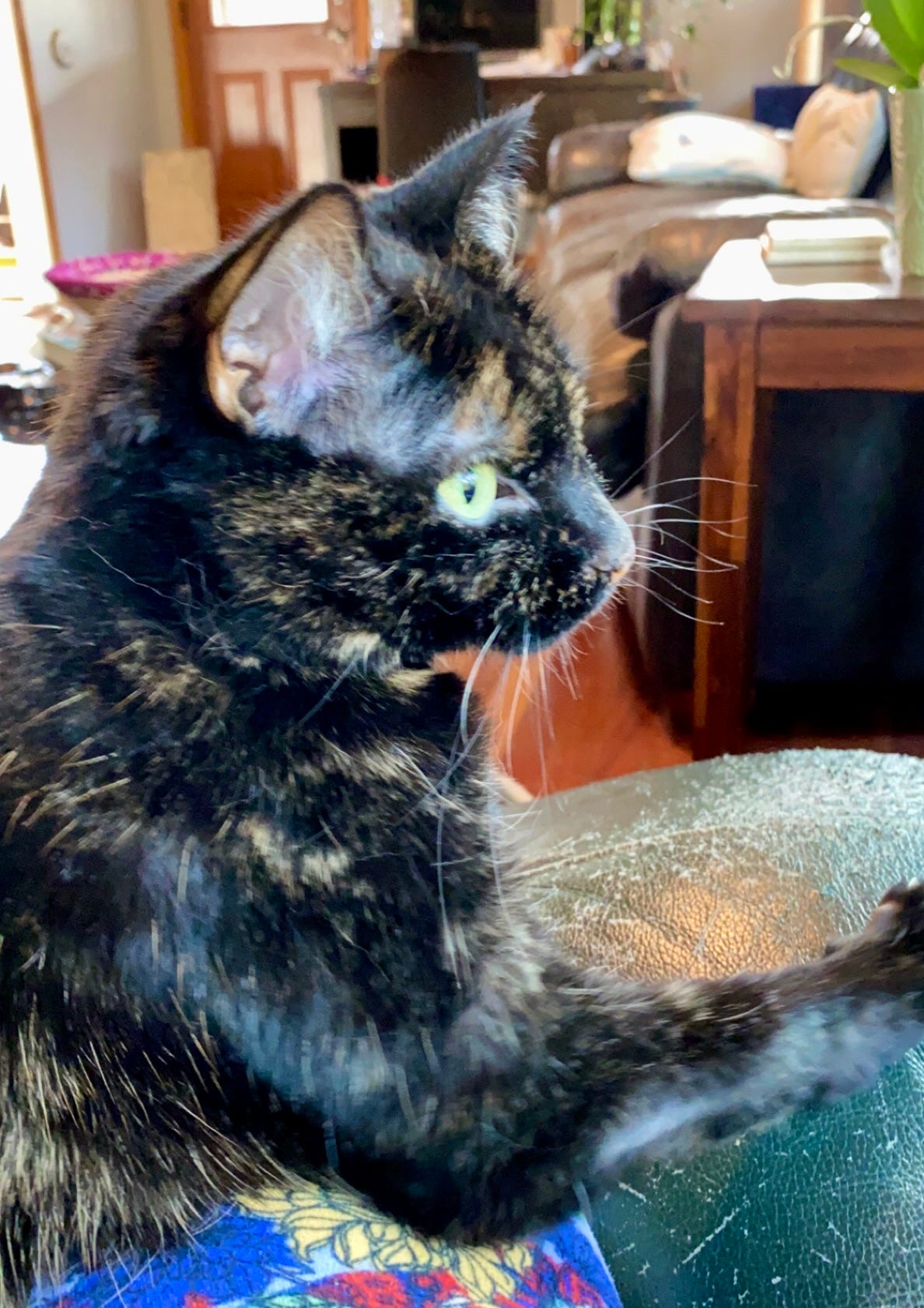

Today, cried into my tortoiseshell’s fur not just for her. I cried because death sucks. Goodbyes hurt, on either side of the equation—the one doing the leaving or the one being left. I know popular culture tells me that “death is just a part of life.” Anyone who tells you this doesn’t have a good grasp of the word “life.” Also, they have bad theology.

How do we hold the tension between raging against death and seeing people (or cats) fully enough to let them go?

Maybe by the time I sit cradling this tiny cat, I’ve learned. I see her pain, and seeing it clearly gives me the power to put it above my own. While she’s still been agile, while she’s still jumped on my lap and purred, while, despite her fragility and her loss of appetite, she could be snarky with the new cats in the roost, I knew this old girl still loved life enough to want to be a part of it.

Today, I’m not sure of those things. Today, though, I know that letting go isn’t acquiescing. It’s being outside the box, refusing to see her through my own hurt. This applies, I feel, to a lot of human goodbyes too, even those that aren’t as final.

How does one know how to do what we were not created to do?

We don’t. That’s the stunning vision we’re granted in our window into Jesus’ grief. Jesus gives us all permission to lament as loudly and long as we wish, knowing the universe’s sustainer grieves with us. As a culture, we’re too quick to be quick. Too eager to rush past the grief and into the whatever comes next. We apologize when we cry at a funeral, as if showing sadness is a mark of weakness and grief is an extraordinary thing to display at the side of a casket. God’s display of grief invites our own at the enemy who always comes too soon. Sunday we said a prayer of memento mori and pondered the idea that death is not a finality but a transition. I had no idea when i planned that a month ago how timely and healing I would find it.

We take care if we, or someone else, notices us slipping into mental health distress. We seek help. We are granted, though, freedom to rage against the dying of the light because death deserves our rage. Mourning has no claim on the light. I know how to let go now. But I’m also learning again how to wail.

Postscript: Barely a few hours after I finished writing this, our tiny bundle of tortitude died. I watched the light leave her eyes in a moment both profoundly holy and painful. They’re not necessarily separate things.